I once cheerfully disenfranchised my whole family. We were taking a vote on something trivial: what movie to watch—Mulan vs. Aladdin. My husband and kids voted for one movie. I voted for another. Gleefully, the kids crowed about winning. I doubled down.

“Put your hands down!” I ordered. I pointed to the twins. “You two aren’t old enough to vote.” Then I pointed to my husband. “And you can’t vote in this country because you’re English. Since I’m the only one in this family both old enough to vote and a citizen of the United States, I win!”

See how easy it is to make it hard to vote? There are all sorts of ways that people can try to take away your vote. Gerrymandering is a fun one. We once lived in Pennsylvania. After we left, the district we were in became one of the most gerrymandered in the United States. The press called it “Goofy kicking Donald Duck.”

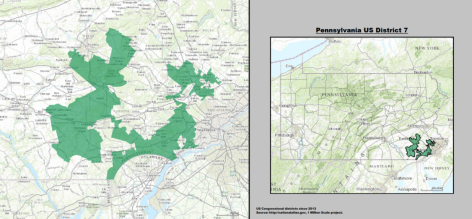

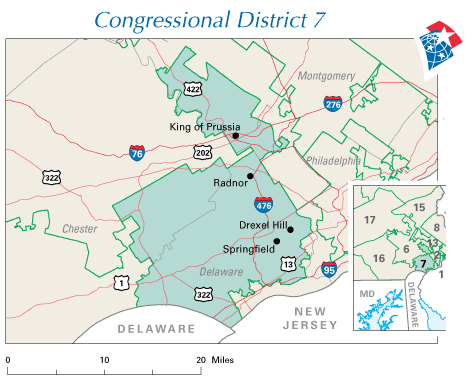

Donald looks more like Stitch to me, but regardless, the Republicans in Pennsylvania cheerfully created this district to give themselves more seats in the legislature by grouping together as many Republican votes as possible. Here’s how District 7 looked prior to this 2003 gerrymandering.

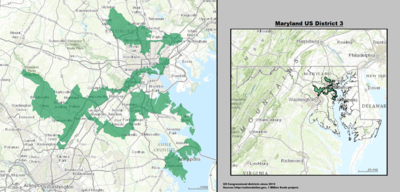

And when we lived there, the district had even more regular boundaries than that! But lest you think this is only a nefarious plan on the part of Republicans, the Democrats are guilty too. Here’s Maryland’s District 3, which a local politician once said looked like “blood spatter from a crime scene.”

Of course, gerrymandering is not a recent phenomenon; in fact, it takes its name from a former governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry. Gerry was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and James Madison’s vice president, but he’s most remembered as the governor whose administration enacted an 1812 law that created more senatorial districts in Massachusetts, thus giving his party more votes. Since one of the newly created Boston-area districts was said to resemble a salamander, the press dubbed it a “Gerry-mander.”

Elkanah Tisdale political cartoon of the “Gerry-Mander”

But gerrymandering is only one way to favor a particular outcome in an election. If you can’t redraw the map to make it harder for your opponents’ votes to count in the newly rigged district, you could try implementing a voter ID law. Twelve states, all Republican held, now have strict voter ID laws where voters have to show an approved ID to vote. Eight other states (six Republican, a swing state, and a Democratic state) require the ID, but they will allow voters to cast a provisional ballot without it. The problem here is that voters have to return with a valid ID within a certain time frame (usually a few days) for the provisional ballot to be counted. Which ID is valid varies by state. In Texas, for example, you can show your gun permit, but your university ID doesn’t count.

Opponents liken this mandatory voter ID system to a poll tax because the voter usually has to pay for the ID, and it is often inconvenient for voters to get because they have to go to a centralized location. Poll taxes (essentially a fee for voting) began in the late 1800s in the South as a way to keep African Americans and poor whites from voting, although the latter might be “grandfathered in” if they had a relative who voted before the Civil War. The legality of the direct fee-to-vote system was struck down by the 24th Amendment in 1964. So of course, proponents of strict voter ID laws argue that these laws are not a poll tax at all; after all valid government ID is useful in other situations besides voting. But an analysis of the effect of voter ID laws show that, like the poll tax, they disproportionately prohibit minorities, students, and the poor—the very people who struggle most to find transportation to a state-approved ID facility and the money to pay for the ID—from voting.

While you might think these voter ID laws are a legacy from years ago, they are actually a relatively new voter suppression tactic. Indiana was the first state to pass a strict voter ID law in 2005. The Supreme Court upheld the law in 2008, and additional states have piled on since. Proponents argue these ID laws are important for preventing voter fraud at the polls, but study after study has found there are actually very few instances of impersonation voter fraud—the type that a voter ID would prevent. According to Justin Levitt, a professor with Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, that number is 31 attempts in more than a billion ballots cast since 2000. That result doesn’t even round to a hundredth of a percent; it is basically zero.

If you’re not a fan of looking at terrible voter ID pictures, you might choose to make it physically harder to vote. You can do that by closing polling places or shortening the hours of voting (both in the period leading up to the election when absentee ballots are cast and on the actual day of the election). This tends to create long lines, causes confusion on where to vote, and often forces the voter to have to travel farther to get to the polls. Again studies show this tactic disproportionately affects minorities and the poor. In the South alone, after part of the Voting Rights Act was struck down in 2013, almost 900 polling places were closed in areas that served these populations in the period leading up to the 2016 election.

And if you find it too much trouble to close down the polling places, you can always just drop people from the voting rolls (sometimes without telling them), prevent released convicts who have served their sentences from ever voting again, change the rules about how the voter has to go about registering, or any number of other methods politicians use to keep people from voting—usually in the fear that the masses won’t vote for their candidates and thus the only way to win is to game the system.

Sure, it feels great for a minute or two to win that election because you suppressed the vote (after all, I still feel sure my favorite Disney movie, Mulan, is superior to Aladdin,* one of the kids’ favorites [Mulan is literally a kick-ass female lead; what’s not to love?]), but if we disenfranchise other voters, a tenet of our democracy is lost in the process. If the politician (or parent) has to rig the system to win, they aren’t really representing the will of the people. In the years since the movie incident, I’m pleased to report that my husband became an American citizen and the kids are now duly registered voters. Their votes each count equally to mine, and that’s how it should be.

On Tuesday, November 6, voters will once again head to the polls to vote in the midterm elections. As we’ve seen, plenty of people want to suppress your vote. Don’t let them. Please check your local requirements and take the time to let your voice be heard. It belongs to you alone, and it matters.

Text © Rebecca Bigelow

Photos from Wiki Commons

Additional Reading

- http://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/vote-voice/keeping-vote/state-rules-federal-rules/poll-taxes

- https://ivn.us/2018/05/09/voter-suppression-politicians-war-vote/

- https://morethanthecurve.com/opinion-piece-weve-been-gerrymandered-bracken-babula/

- https://newrepublic.com/article/109938/marylands-3rd-district-americas-most-gerrymandered-congressional-district

- https://www.aclu.org/other/oppose-voter-id-legislation-fact-sheet

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/gerrymandering

- https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/665966.pdf

- https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/how-the-gop-rigs-elections-121907/

- https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/11/4/13501120/vote-polling-places-election-2016

- https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/11/7/13545718/voter-suppression-early-voting-2016

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/08/06/a-comprehensive-investigation-of-voter-impersonation-finds-31-credible-incidents-out-of-one-billion-ballots-cast/?noredirect=on

*Hey, Aladdin fans, I like your movie pick. I just like mine more! YMMV.