My father swore the secret was the seaweed.

Donning his custom “Bakemaster” apron,

He’d first dig out a pit in the driveway,

Then lay a fire in it, setting each split log just so.

Next a half barrel, of uncertain provenance,

Appeared each year and was settled on top.

Bricks were laid in the steel bottom to retain heat.

Then came the seaweed, dampened with a garden hose.

My father swore the secret was the seaweed.

Next layers of offerings from Poseidon, Neptune:

Lobster, steamer clams, fresh from the dock,

Followed by butter and sugar corn, new potatoes, yams.

With each layer kept separate from the rest

By a buffer of seaweed, dampened with a garden hose.

My father always swore the secret was the seaweed.

Then the whole epicurean treasure chest was covered in burlap.

My father, and my cousin—the bakemaster’s assistant—

Attended to the fire, to the moisture level of the burlap.

While woodsmoke and steam lazily entwined,

we kids were press-ganged into cranking ice cream,

Taking turns with vanilla, chocolate, and banana.

When Dad announced the feast ready for the masses,

And kith and kin, family and friends, had gathered,

He’d preside over the table and intone:

“May everyone have it this good.”

Then butter dripped from claw meat and corn cob,

And compliments flew.

But Dad dismissed the praise, with a smile and a shrug.

The secret, he’d say, is in the seaweed.

Category Archives: Holidays

On All Hallow’s Eve

The artist down the street

Gave delicately iced, arched-back

Black cat sugar cookies.

The people in the castle

Gave homemade popcorn balls

That stuck in your teeth.

The neighbors ’cross the way

Gave gooey caramel apples.

But we always hoped for

Store-bought candy.

And now, you can’t give

Hand-crafted goodies

Because parents are afraid

Of razors in apples,

Or drugs in cookies,

Or worst of all,

Of not knowing

All the people

In the neighborhood.

I guess irony is knowing you

Only wanted Snickers as a kid,

But as an adult, you are sad

That homemade sweets

Have gone the way of the dodo

At Trick-or-Treat.

Text: © 2017 Rebecca Bigelow Clipart: WikiClipArt

Pilgrim’s Progress

When the Pilgrims and Native Americans sat down at their three-day celebration to give thanks for a bountiful harvest in 1621, they could not have imagined the trappings of a modern thanksgiving. Football? Green bean casserole? A 2.5 mile parade through a metropolis? All inconceivable!

More than 200 years later, the idea of our modern-style Thanksgiving gained traction when it was made a fixed national holiday in the United States by Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Football on Thanksgiving came a few years later in 1869, but green bean casserole wasn’t invented until 1955. In between the two latter dates, R.H. Macy loaned his name to the best-known holiday parade in the United States when employees organized the first procession to Macy’s flagship store in New York City.

Will It Play in Peoria?

Although the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade is now synonymous with Thanksgiving and is the way millions of Americans herald the holiday season, it isn’t the longest running holiday parade in the United States. That honor belongs to the Santa Claus Parade in Peoria, Illinois, which is now held the day after Thanksgiving and first welcomed Santa in 1889 (versions of the parade were held in both 1887 and 1888 to celebrate first the groundbreaking and later the completion of a new bridge, but St. Nick was not featured).

And despite the Macy Parade’s starring role in 1947’s Miracle on 34th Street, Macy’s wasn’t even the first parade held on Thanksgiving day. Ironically, that honor belonged to Macy’s real life—and reel life—rival: Gimbels, which first held their parade in 1920 in Philadelphia. Ellis Gimbel attracted children (and their parents) to his toy department with a parade that included 15 cars, 50 people, and the jolly elf himself. Philadelphia’s Thanksgiving parade remains the longest running one in the country, although since the demise of Gimbels stores in the 1980s, the parade has been renamed several times to recognize new sponsors.

Broadway Debut

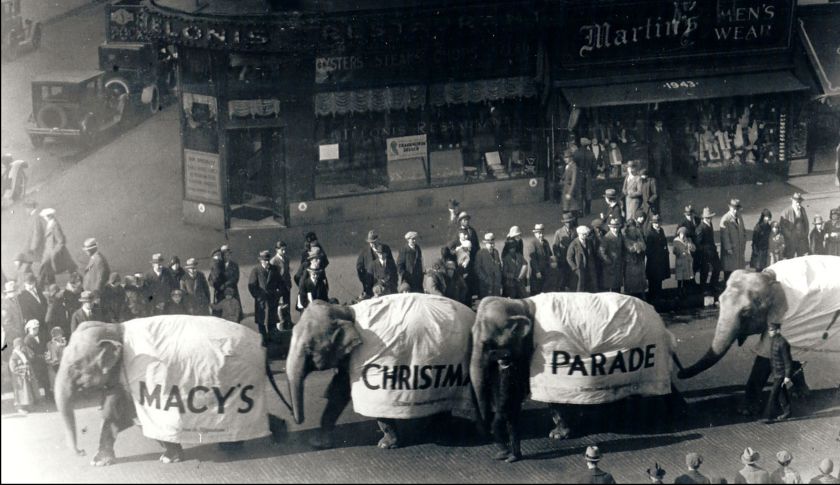

Four years after Gimbels’ first parade, in 1924, New York Macy’s employees held their first attempt, but the parade didn’t look much like the one held today. Although held on Thanksgiving, it was called a Christmas parade, and it was held without balloons. The route, which ended at the Herald Square Macy’s—as every Macy’s Parade since has done—began not at 77th Street as the parade does today, but at 145th Street and Covenant in Harlem, making the original route more than six miles long (or more than twice as long as today’s approximately 2.5 mile route).

Elephants from the Central Park Zoo.

Kris Kringle—already the main event—was brought in by “a retinue of clowns, freaks, animals and floats,” according to an article in The New York Times. The freaks were not explained, but the clowns were costumed employee volunteers, the animals were borrowed from the Central Park Zoo, and the floats had a Mother Goose theme to match the decorated Mother Goose Christmas–themed windows at the Macy’s store. Crowd estimates were put at 10,000 in Herald Square and another 250,000 along the route.

The first Santa float.

The first Santa float.

Once Santa arrived, he was crowned “King of the Kiddies.” The event was declared a rousing success, and Macy’s vowed to repeat the effort the following year. Indeed they have done so every year since, with the exception of the years 1942–1944, when the rubber and helium used in the parade was deemed more valuable to America’s war effort than to the parade. Interestingly, however, both Philadelphia’s and Peoria’s parades continued through the war years uninterrupted.

So Much Hot Air

Freaks notwithstanding, the Macy’s parade began to look less like a circus parade and more like the modern version in 1927—the first year balloons were used. The early balloons (four in the 1927 parade, including a dragon and Felix the Cat) were brought to the parade by puppeteer and theatrical designer Anthony Sarg. They were small, filled with air, controlled like a puppet by the volunteer handlers, and were more like floats (falloons, in modern terminology) than today’s high-soaring balloons.

The Felix the Cat balloon. Look, Ma! Only four handlers.

The Felix the Cat balloon. Look, Ma! Only four handlers.

Still, the cat was out of the bag, and the live animals were permanently retired to the zoo. Helium was added to the balloons a year later and has been used every year the parade has run since, with two exceptions: In 1958 a helium shortage force parade organizers to transport the air-filled balloons on trucks and with cranes, and in 1971, high winds grounded the balloons.

Helium tankers deliver the gas to the public balloon inflation on Wednesday.

Helium tankers deliver the gas to the public balloon inflation on Wednesday.

Balloons and floats for the modern parade are all created at Macy’s year-round parade studio in Hoboken, New Jersey. After several accidents in high winds, balloon size has been reduced, the number of handlers required for each balloon has been upped to a minimum of 50, and the balloons must be tethered to a vehicle, not just people. Additionally, traffic signals are turned out of the path of the parade or removed altogether, and the balloons are grounded if winds are sustained over 23 miles per hour. Floats have their own requirements on size, but the elves at the Hoboken studios make them so they fold up to 12 feet by 8 feet so they can fit through the Lincoln Tunnel on their way to and from the parade.

Notice the traffic lights have been moved out of the way.

Notice the traffic lights have been moved out of the way.

No Strings Attached

How much does it cost for Macy’s to create a balloon or float? Well, Macy’s is notoriously tightlipped on this matter. They have stated that they consider the parade to be a gift to the people of New York and the viewers at home, arguing that a gift giver does not announce the price of the gift to the recipient. Still, there are estimates that a new balloon will cost the sponsor as much as $190,000, with a repeat entry coming in around $90,000. A float is said to average $60,000.

In 2015, the balloons are a lot bigger and require many more handlers than in the earliest parades.

The performers are volunteers—mostly with Macy’s—but the groups that come to the parade, like a marching band, pay their own expenses. Last year, the University of Virginia marching band estimated their trip cost would be in the neighborhood of a quarter-million dollars. Groups that come from farther away have higher costs. Stephen F. Austin State University, which came from Texas, estimated their costs at more than $1,500 per person for their more than 300 band member because they had to charter planes. The University of Illinois’ Marching Illini did not announce a final price tag, as fundraising covered most of the expense for their trip, which included seven charter buses, meals and hotels, rehearsal space, and more, for approximately 400 people in the band organization for their four days in New York.

In exchange, after weeks of practice and hard work, and a two or three a.m. rehearsal in front of Macy’s for the live performers, each balloon, float, or band is rewarded with a few seconds of television coverage on Thanksgiving morning. In fact, each band was allotted one minute and fifteen seconds for their Herald Square performance this year. It may seem like a lot of work for little reward, but 175 bands auditioned for the chance to participate this year. Twelve were accepted. Macy’s has no shortage of bands, performers, and sponsors that want to be part of this annual holiday tradition.

I Always Think There Is a Band Kid

As traditions go, I confess, I think football should be a 15 minute game played between two halves of a marching band concert, and I think green bean casserole is an abomination to green beans. But I love a parade. And the approximately 3 million people who lined the streets of New York and the millions of viewers on TV who made last year’s Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade the highest rated non-sports show of the fall season agree with me.

Text ©2016 by Rebecca Bigelow;

Historic photos (1–3) Macy’s Public Domain;

Remaining color photos ©2015 by Rebecca Bigelow and Ian Brooks

Additional Reading:

Early Parade Information:

- Peoria Santa Claus Parade

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- “Greet Santa Claus as the ‘King of the Kiddies,” The New York Times, November 28, 1924.

Information on Parade Costs:

Macy’s Parade Tidbits:

2015 Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade Marching Band Info

A Bit of Doggerel

It’s Valentine’s Day—at least for a few more minutes. If the checkout line at the grocery store yesterday is any indication, lots of people got stuffed animals and big pink cards covered in glitter (lots of glitter) in my town today. I tend to prefer a more low-key day (because I am too frugal to see much point in buying a card for eight bucks that will be looked at once!), so my day was perfect for me: No grand gestures, just dinner with my husband and son and a chance to Skype with my daughter who is away at the moment. Spending that kind of time with loved ones is definitely my idea of a successful holiday. Whether you celebrated romantically with a partner, as part of a family gathering, with a friend or two, or just enjoyed alone time, I hope your day was as perfect for you as mine was for me.

Although my Valentine’s Day was lovely, there have been some irritants in the last couple of weeks. What better way to slay those dragons than with a bit of fluff and fun? I think I’ll call this collection Poems from Cranky People. Writing them made me feel better. I can guarantee these little bits of verse will not end up on a card you can buy at the grocery (not in pink, not at any price, and they are definitely glitter free), but perhaps they’ll make you smile. Enjoy the last few minutes of the holiday!

Foreshadowing by Rebecca Bigelow

Each February we pretend

That some rodent can portend

The duration of our wintry state.

But I wish it would prognosticate

Something of more import.

So if, in fact, we must resort

To using a groundhog named Phil

To predict the future, then he should spill

Whether we will suffer, over our objections,

At least six more months of politics and elections.

Lightning Bugs by Rebecca Bigelow

A light glows briefly in the dark.

And like the mating call of a firefly,

Another answers it.

And soon the lights are twinkling.

Everywhere.

Some flashes last mere milliseconds.

But some can be measured

In moonlights and cups of cocoa.

And I wonder why

It is so important

To check your damn phone

In the theatre.

The Ballot Box

Monday was President’s Day. In 1968, Congress passed a law that created uniform Monday holidays (to create three-day weekends) and moved the holiday for Washington’s Birthday to the third Monday in February. The law went into effect in 1971, but Washington’s Birthday gradually morphed into a day to celebrate all the presidents. Washington’s loss is the perfect excuse for a quiz on some modern US president. (What? Monday was a holiday. You had an extra day to study!) For each question, vote for Teddy Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, or Harry Truman. Highlight the text below each question to see the answers.

1. Which President ordered the Berlin Airlift?

Other leaders suggested sending supplies to cutoff West Berlin in trucks protected by tanks, but Truman feared this could start a new war. He ordered the airlift instead. To bring in the more than 2 million tons of food and coal to West Berliners, American and British planes at the height of the airlift were landing every three minutes. The success of the airlift made the Russian blockage ineffective and let the West win the propaganda battle in this cold war skirmish.

2. Which president ordered the use of the atomic bomb against Japan?

At the Potsdam Conference, Truman hinted to Josef Stalin that the USA was developing a powerful new weapon. Stalin pretended to be uniformed, but he actually knew about the atomic bomb before Truman did! Stalin had spies in the US nuclear program; Truman, on the other hand, learned about the bomb only after his inauguration as president. His decision to drop the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki remains one of the most controversial decisions ever made by a president.

3. Which president is the only one to hold a PhD?

Did you guess Truman again? Wilson actually earned his PhD from Johns Hopkins. His first job was as a professor of history and politics at Bryn Mawr–a women’s college established by Quakers in Pennsylvania. Wilson didn’t particularly care for teaching women, however, writing to a friend, “My teaching here this year lies altogether in the field of political economy, and in my own special field of public law: and I already feel that teaching such topics to women threatens to relax not a little my mental muscle.”

4. Which president once owned a haberdashery?

Truman’s partner in the business was a war buddy named Edward Jacobson. The business failed, but the friendship remained. Jacobson, who was Jewish, would play an important role in 1948 when Israel came into existence, helping convince Truman to recognize the new country. Despite opposition from his advisers, Truman announced that the United States would recognize Israel a mere eleven minutes after the Israelis announced the new country.

5. Which president changed his mind about women’s suffrage during his two terms in office?

Wilson modified his stance on women’s voting rights. At first, Wilson was embarrassed by the suffragettes and did not support their cause. (See his comments on the education of women earlier in this quiz.) After the United States entered World War I, however, he asked Congress: “We have made partners of the women in this war. Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil, and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Despite this, women would have to wait until after the war for the Nineteenth Amendment to pass.

6. Which president was an avid conservationist?

As president, Teddy Roosevelt doubled the number of National Parks and created over fifty Federal Bird Reserves. He also introduced the Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906. This granted him the executive power to create national monuments at historically or scientifically interesting sites. This allowed Roosevelt to preserve sites like Devils Tower in Wyoming, the Petrified Forest in Arizona, and a large area of the Grand Canyon.

7. Which president created projects that benefited National Parks like Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee?

If you guessed Teddy Roosevelt again, you guessed wrong. His cousin Franklin Roosevelt created an alphabet soup of programs and policies, known as the New Deal, that were designed to shore up banks, help with unemployment, and stimulate the economy. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was part of the New Deal, was a popular program that created jobs through public works projects. Roads, fire towers, and tree plantings were just a few of the projects the men of the CCC completed in National Parks, such as Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee and the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia.

How did you do? Are you a presidential scholar or do you need to revisit history class?

Text: Rebecca Bigelow; picture is in public domain.

Additional Reading:

Penicillin—A Love Story

This week’s entry is a little late, but I have a good excuse. In researching this week’s topic, I stumbled upon a medical mystery. Here’s the story …

February 14 is Valentine’s Day—a day for chocolate, roses, and romance. But my Valentine was winging his way to Vienna for work. (I know. But someone has to do it!) So for me, there was no chocolate. No roses. No romance. (Full disclosure: we did share a heart-shaped pizza a couple of days before he left and exchanged eCards on the day.) Ordinarily a holiday would be a great blog post, but I didn’t feel much like writing about the history of the day meant for kisses and sweet nothings. Although I could have played up the really gory aspects—beheaded priests and all that (True story. But maybe next year.)—I decided to see what else happened on February 14 (besides the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, which has been done to death [Rimshot!]).

And there it was on the History Channel’s This Day in History website: February 14, 1929—Penicillin Discovered. Awesome. I can’t take it—I’m allergic—but I can write about it. So, as any good historian would do, I began to investigate the facts of this premise: penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming (1881–1955) on Valentine’s Day in 1929. The trouble began with the sources. I could find dozens, hundreds and thousands even, that made similar claims to the History Channel, but I couldn’t find any primary source material to back it up.

Discovery

Digging deeper, I determined Fleming had actually made the discovery in September 1928. He was studying bacteria at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, England, and he noticed odd patterns in one of his cultures that had been contaminated by spores of Penicillium (likely from another lab in the building). The Penicillium mold prevented the Staphylococcus bacteria from growing in an area around the spores. Further experiments by Fleming followed, and he learned that the mold was harmless to animals and prevented Staphylococcus growth even when diluted. He also noted that the penicillin (Fleming’s name for the active substance) was not very stable because it quickly lost strength.

Obviously then, Fleming did not discover penicillin on Valentine’s Day. I returned to the sources. Some said he actually “announced” the discovery on February 14. Possible. I started a new line of research. Perhaps his first paper on the subject was published on February 14, 1929. Again, I was stymied. Fleming’s work first appeared in The British Journal of Experimental Pathology, which helpfully noted the article had been “received for publication May 10, 1929”—definitely not Valentine’s Day.

Endeavor

More research followed—for me and for penicillin. I read about the other investigators who helped to develop penicillin, including Oxford University researchers, Howard Florey (1898–1968) and Ernst Chain (1906–1979). In a collaboration that began in the late 1930s, Florey and Chain (and others in their lab) purified penicillin and discovered therapeutic uses; however, production and scale were still issues, especially with the start of World War II (1939–1945) in Europe. These problems would be solved in partnership with a lab in Peoria, Illinois, and large scale production would go on to save many soldiers from infection during the war and many civilians in the years after.** Fleming, Florey, and Chain won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945 for their contributions.

Fleming, a modest man, remarked: “I did not invent penicillin. Nature did that. I only discovered it by accident.” But it would probably be more accurate to say he rediscovered it. It turns out that Fleming was not the first person to note the abilities of Penicillium! Others had witnessed molds’ healing ability, including a medical student, Ernest Duchesne (1874–1912), whose thesis, “Contribution to the study of vital competition in microorganisms: Antagonism between moulds and microbes,” also considered the therapeutic values of molds. The year? 1897. And there were others before Duchesne. Unfortunately for modern medicine, Duchesne died before he could continue his research, and Duchesne’s work went largely unnoticed at the time. It took Fleming and his contaminated sample to get the idea noticed.

Challenger

But not on February 14! I searched again, trying to find the “patient zero” for the History Channel article. Who had Fleming told on February 14? His wife? The milkman? The story must have started somewhere! I mentioned the problem to my husband (a scientist, but not a bacteriologist) via a Skype chat (because remember he is still in Vienna, poor thing!) and asked him where a British scientist might make such an announcement. He suggested the Royal Society. And I was off pulling another thread in my attempt at unraveling the Valentine’s Day conundrum, even though my research had now run to dozens of hours over several days. “Why bother?” You ask. Because (A) I’m frustrated by unsolved mysteries, (B) misinformation irritates me, and (C) I’m stubborn. (Full disclosure: friends and family would probably say it is mostly C!) So now it was a matter of principle!

Cleared for Launch

I checked the records of the Royal Society. Nada. I searched for medical conferences held in February 1929. Zilch. I planned an alternate blog post in case I failed. And frankly, I was beginning to think that was the one that would run. But then, I found it. No fanfare (although I confess, the trumpeters were playing jubilantly in my head!), no ticker-tape parade, just a single reference. Could it be? I checked and triple checked. I wasn’t going to publish this unless I was sure. I found other sources to confirm, and I am pleased to announce the following:

Alexander Fleming presented some of his work on penicillin at the Medical Research Club in London on February 13, 1929.

That’s right. The day before Valentine’s Day. Where the Valentine’s Day mythos began is anyone’s guess. Perhaps someone thought it would be funny if the antibiotic that cures some sexually transmitted diseases was discovered on Valentine’s Day and fudged the date. Perhaps the initial error was a typo. Perhaps, it was lazy research. Regardless, the premise that penicillin was discovered (or even announced) by Alexander Fleming on Valentine’s Day in 1929 is completely debunked. Sorry History Channel. I know it’s a bitter pill to swallow.

Text: ©Rebecca Bigelow

Photo: Alexander Fleming in his lab.

Original via Wikimedia; edits Rebecca Bigelow.

**On a personal note, penicillin came to the market too late to save my uncle (on my father’s side) who died in 1931, at the age of six, from complications from strep throat. Penicillin probably would have saved him, but 1943 was the year mass production of penicillin began—coincidentally, the year my father turned six.

Additional Reading:

This Day in History

- The History Channel website article that started this quest.

- One of the many sites that said Fleming “announced” the discovery on February 14.

Fleming and Penicillin History

- Fleming, Alexander. 1929. “On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to Their Use in the Isolation of B. influenza.” British Journal of Experimental Pathology 10:226–236. (The first page of Fleming’s original paper. A full reprint is available on JSTOR.)

- Harris, Henry. 1999. “Howard Florey and the Development of Penicillin.” Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 53(2):243–252.

- The Nobel site with information on Fleming, Florey, and Chain.

- More on Fleming.

- Discussion of Penicillin Production.

- Information on Duchesne’s Thesis.

- Brief biography of Duchesne.

Some of the Sources for February 13, 1929

- Greenwood, David. 2009. Antimicrobial Drugs: Chronicle of a Twentieth-Century Medical Triumph. Oxford University Press, 88.

- Hare, Ronald. 1979. “Penicillin—Setting the Record Straight.” New Scientist 81(1142):466–68.

- Hare, Ronald. 1983. “The Scientific Activities of Alexander Fleming Other Than the Discovery of Penicillin.” Medical History 27:347–372.

- Lightman, Alan. 2010. The Discoveries: Great Breakthroughs in 20th-Century Science. Random House Digital.

Wild(life) Weather

February 2 was Groundhog Day. The day plays host to a somewhat bizarre ritual in the United States and Canada in which people haul a rodent out of its burrow and hold it up to see if it sees its shadow. Tradition holds that if the groundhog sees its shadow, we get to suffer through six more weeks of winter. No shadow? Early Spring! On Saturday, Punxsutawney Phil, the most famous of the groundhog prognosticators, predicted early spring. Woot! But it turns out Phil is right only about 40 percent of the time.

Phil-osophy

In fact, I’ve long thought that if Punxsutawney Phil’s people flipped the predictor, Phil would be far more precise. After all, if the groundhog sees his shadow, the sky must be clear. Surely a sunny February 2 is a better forecaster of early spring than a cloudy one? It seems, however, that part of the legend has its basis in European folklore. Candlemas, a Christian observance (mixed with Pagan practice) where people would have their candles blessed, marked forty days after Christmas and the midpoint of winter. Candlemas also falls on February 2, which is roughly half way between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox. Candlemas, like Groundhog Day, has its own weather-predicting traditions. There were rhymes, variously worded, but similar to this:

If Candlemas be fair and bright

Winter will have another fight.

If Candlemas brings cloud and rain,

Winter will not come again.

Sound familiar, Phil? And in Germany, they believed that a badger (some sources say a hedgehog, and I suppose one must use whatever small animal is most readily available) seeing its shadow would bring more winter.

Re-Phil

This brings us back to Punxsutawney. In the 1800s Germans immigrated to the United States and many settled in Pennsylvania (becoming known as Pennsylvania Dutch or Pennsylvania German for the dialect they spoke), bringing their traditions with them. In Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, however, people were more likely to eat Phil’s ancestors than seek weather advice from them—at least until a local newspaper editor got involved. Clymer Freas was the editor of the Punxsutawney Spirit. He endowed Phil with weather wisdom, created Phil’s abode in Gobbler’s Knob, and promoted the first official ceremony, February 2, 1887, in the paper. Today, thousands (an estimated 30,000 on Saturday) descend on Punxsutawney for the festivities.

Phil-ibuster

All those town visitors bring in tourism dollars. Other areas, not to be out done, decided their own groundhogs (also known as woodchucks or marmots) were equal to the task of weather prophecy. Chattanooga Chuck, Stormy Marmot, Balzac Billy, and General Beauregard Lee are among the soothsaying Sciuridae (yes, groundhogs are members of the squirrel family) that are looking to stage a coup and reign in Phil’s stead as king of Groundhog Day.

Ful-Philled

Still, Phil probably doesn’t have to worry about these pretenders to the throne. It’s more likely Phil will be put out of business by climate change. The winter of 2012 was the fourth warmest on record in the United States (2000, 1999, and 1992 were first, second, and third, respectively). 2012 was actually the 36th consecutive year where global temperatures were above average. If this trend continues, Phil can perpetually pick early spring and retire. Or, if we insist on having a weather rodent, we can choose a tropical replacement. May I suggest the Asylum (PA) Agouti*?

*Asylum, Pennsylvania, is a mere 200 miles from Punxsutawney. An agouti, besides being an excellent crossword puzzle word, is a rodent native to Central America, the West Indies, and northern South America.

Text: © Rebecca Bigelow

Groundhog photo: © Matt MacGillivray (qmnonic)

Additional Reading:

- Punxsutawney Phil’s official website.

- Punxsutawney and Groundhog Day History.

- Information about Candlemas.

- NOAA Climate Data.

- Guardian (UK) Groundhog Day Data article.

- Actual Data spreadsheet from Guardian (UK).

- Agouti Fact Page from the San Diego Zoo.